Ashley Logan’s latest poetry collection, The World Goes Down Slow, is a profound exploration of healing and self-discovery. Rooted in her personal journey from pain and grief to peace and health, Ashley’s work is a testament to the power of writing as a means of processing and overcoming life’s challenges. Through vivid imagery and heartfelt introspection, she transforms her experiences into poems that resonate with universal themes of growth and resilience. In this interview, Ashley opens up about her creative process, the role of nature in her healing, the challenges she faced while compiling her collection, and offers valuable advice to aspiring poets navigating their own struggles.

You mentioned that your poems reflect your journey from pain and grief to a place of health and peace. Could you share a bit about the emotional and creative process behind transforming your experiences into poetry?

When I was a child, I kept a lot of diaries. Part of it was that I loved to read and wondered about the magic that went into making all the books that I adored. The other part was that I went through a time where I wanted terribly to be Harriet the Spy and solve mysteries with the assistance of a well-loved and oft used notebook. Eventually, I turned inward and tried solving the puzzles of my experiences that were much too large for a child to understand at that time. I sorted through how I felt through writing, and the older I got, the more I found that my own words gave me power over my truth. It is difficult to not feel safe enough to express yourself, so the diaries gave me that freedom, that sanctuary. To look back over those words and be able to know: this happened to me; this is how I feel; this is what I need; this is what I hope for… it was no small thing. I still write everything down, whether in a journal or in the form of a poem or as pieces of myself implanted into a novel. In doing so, I can acknowledge my journey and not withhold any part of myself and what I know to be true. Over the years and in my latest collection, The World Goes Down Slow, I have excavated the bones of my past, brushed them off, and assembled the pieces like skeletons on display of every chapter that led me to here. It is a painful and humbling experience, and I think grief goes hand in hand with healing at times. Writing my book certainly made me feel that way, but I know I am better for putting in the energy to dig back into my life — it is the truest thing I have written to date, which has given me enough peace to salve old wounds and also move on in my journey.

Nature seems to play a significant role in your work and healing process. How has your connection with nature evolved, and how does it influence your writing and perspective on life?

Like many millennials, I think, I was a latchkey kid growing up and loved playing outdoors at every opportunity when I wasn’t reading (although sometimes I would do that outside, too). I have a distinct memory of sitting under the magnolia tree on the side of my house and writing down in my notebook how many birds I could see and what they looked like. I don’t recall ever really knowing any of their names except for the Northern Cardinal, but I do remember how much I enjoyed seeing all those little songbirds flit about with their unique calls crossing overhead. Sitting below them and observing, it was as though I was being given the special privilege to access their world. Watching them made me feel light, as though perhaps I could leap into the next breeze and gracefully carry myself wherever I wanted to go next. To now be engaged to a forester who manages a bird sanctuary feels kismet in many ways in retrospect. We enjoy spending a lot of our time traveling, hiking, and rock climbing, the latter of which was a sport that my fiancé introduced me to when we first began dating. Finding solitude in nature is often spoken about, but I think the internal stillness I have been able to find is a striking contrast to the ever-moving, forever changing forms of nature. In my awe over discoveries made while climbing up a mountain tethered by a rope, pushing through the burn in my lungs and legs as I hiked over steep terrain, gliding through rivers and lakes as my hands steadily moved the oar from one side of the kayak to the other, witnessing sights in person that are otherwise impossible without making those efforts and finding mindfulness in the process… it was nature that reminded me of how small I truly am. To be able to visualize that smallness, the simultaneous feeling of insignificance and power, was helpful because it was also so human. It showed me that though I am mortal, I remain part of something that goes well beyond me, well beyond all of us. Though I am not religious, I have discovered that I do believe in faith — a powerful spark for anyone no matter where it is borne from. My faith was found and developed in the reverence for the earth, and so all of this also became incorporated into my work as it continued to heal all that I felt had been broken.

What were some of the challenges you faced while working on this collection, either creatively or personally? How did you overcome these challenges?

When I started writing this collection, it was not with the intention of publishing it as a book. I was burned out personally, professionally, and creatively for a long time so my writing began to occur less and less frequently while navigating some big life changes including major mental health challenges, navigating a new career, going through a divorce, and a move from the place I had lived for over a decade. However, it was those life experiences that also eventually brought me back to myself and therefore help me become strong enough to tackle subjects I had held close to the vest for a long time. This did not happen without a lot of self-doubt, however. It was one thing to write it all down but another thing entirely to consider putting it into a collection that was a tapestry of my life to be read by others. When I recognized I had been writing with a continuous theme of personal and spiritual growth using the natural world as a steady backdrop, however, it was hard to ignore that every poem fit together to make a succinct story of redemption and reclamation of self, of overcoming fear and centering oneself in the ownership that comes with reflection. From there, the challenges evolved into the next steps of publishing, such as revising and then revising some more until I didn’t really want to look at any of it anymore. At that point, I turned it over to another set of eyes while I focused on finalizing the cover design, writing blurbs, setting it up in KDP and IngramSparks, deciding on a launch date, and dreadfully, tackling the marketing beast. Self-promotion gave me a lot of anxiety because I would convince myself the more I talked about this book, despite being immensely proud of its contents, that I should not take up so much space with my words. In those moments, I would flip back through the collection and remind myself it was these kinds of moments I must continue to overcome. I had to determine that the only person who could make that happen was me. It became much easier as I began to trust myself more and believe that all the work I had put into this book was worthwhile — to me, most importantly, before it even reached anyone else.

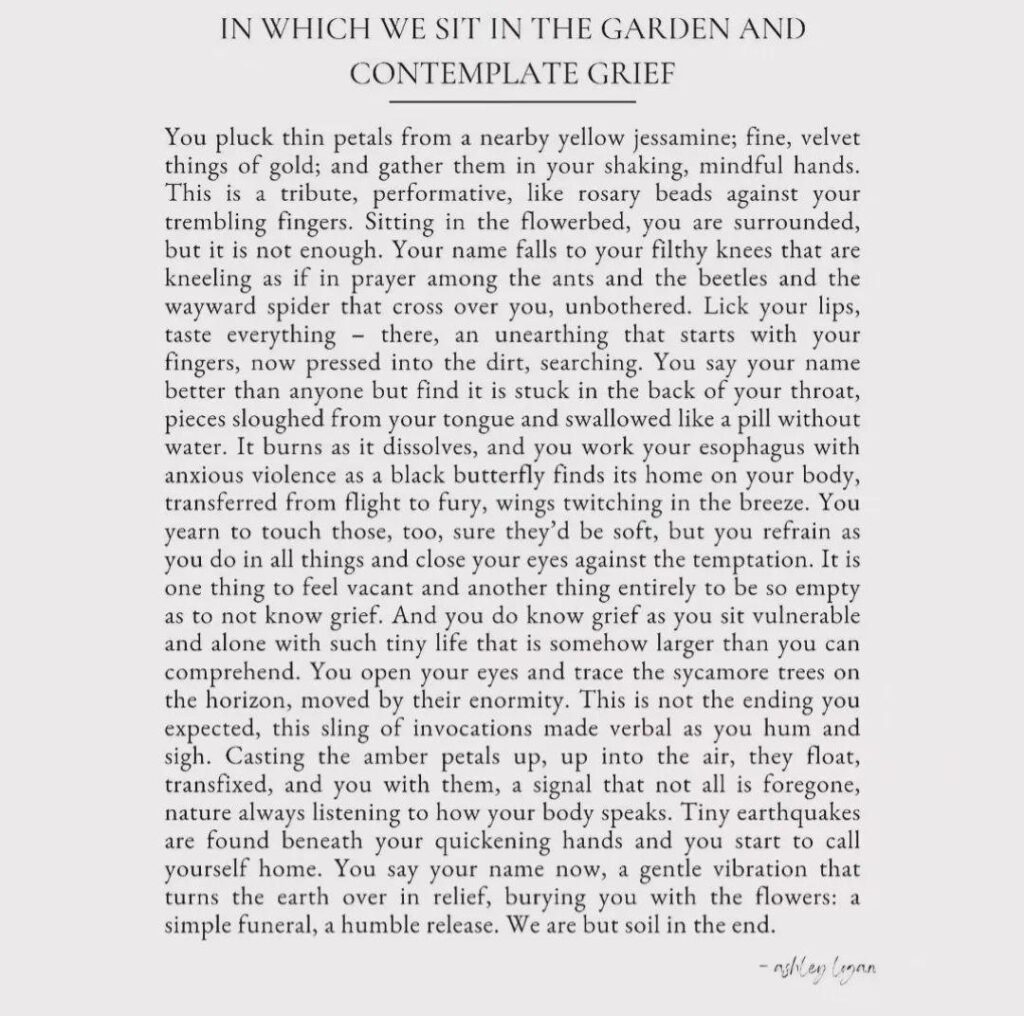

Can you share a specific poem from your collection that holds particular meaning or significance for you? What inspired that poem?

“In Which We Sit in the Garden and Contemplate Grief” is the first poem in my collection because it sets the tone for the themes found throughout the rest of the book. It is also one of the first poems I looked back upon a year or so after I had written it that helped me decide to compile my work into this collection centered around human experience within the natural world. I wrote it shortly after my divorce while in the midst of processing the end of a relationship that began when I was 18 and contemplating “what it all means” and “what is my purpose now” and who I was — on my own with no obligation to anyone but myself for the first time in my life. There was a summer afternoon that I spent lazing alone in the sun and began to meditate without really meaning to, clearing my mind and instead observing my senses. The way the breeze made the trees whisper, the way it brought relief to my warming skin. When I stretched my arms out, my fingers entangled in the grass that was beginning to grow too long again. I felt small beetles cross over my hand and allowed them the experience of a mountain’s magnitude. Turning my face to the sky, I found the way the clouds moved swiftly like leaves atop a river current mesmerizing and calming. They were ethereal visitors that changed shape as they cast slight shadows over my face, a brief shield before moving on. Similarly, the many nearby birds called to one another while cicadas continued their rhythmic songs, and it felt a privilege to be able to listen in on their conversations. It felt a secret to be comforted by such internal quiet and yet discover how much was being said in my surroundings. I simultaneously began to let go of the overwhelming enormity of my life, all that I had been struggling through, and also revel in the small glory of being an individual. To be among nature is to also be part of it and finding meaning in that realization brought me profound peace — with all that came before and with all that was yet to come. I wanted for myself the knowing of every day’s mystery and exploration. I wanted to embrace my curiosity of the world, and it was in those moments laid bare beneath a blazing sun that threatened to burn that I returned home, prepared to stand once more in empowerment. Thus, this poem sprouted from that journey of self-discovery., and ultimately, maintaining stubborn hope and defiant joy until the very end.

Through your journey of healing and self-discovery, what are some of the most important lessons you’ve learned about yourself and life in general?

I learned very quickly that avoidance is a killer of self. There was a lot of trauma, grief, and rage that I had suppressed for the sake of others and had not truly processed for my own sake as well. It was an act of self-defense, of protection from what happens when you face the ghosts that continue to linger and haunt as you struggle to leave them behind. The only way for me to banish them from my mind was to turn back and essentially lead my inner child from where she had hidden and bring her back with me. I discovered so much that I had felt I had lost — things like passion, a sense of adventure, and awe over the unknown. By no longer avoiding my life, no longer avoiding making the decisions that would bring down the broken foundations in my self and in my relationships, I was able to begin the process of rebuilding. It has been difficult work but with every new layer of groundwork, I am strengthened and have become unafraid of standing within my potential. I recognize now that I deserved so much more and should no longer settle for less. There is freedom in allowing yourself to evolve, though change is often painful and therefore easy to struggle against. The reward of healing and discovering who you are, however, is worth all that effort and it is an effort I hope to continue putting forth going forward. The lessons of grace, of forgiveness, of patience have settled deep and are emerging in the energy I put out and in the energy I receive in return. The capacity for learning expands with every new acceptance and I don’t dare suppress what could be beyond those important lessons.

What advice would you give to aspiring poets or individuals who are going through their own struggles and seeking creative outlets for healing?

My best advice is to write it down — whatever the “it” is, write it down. It does not have to be poignant or beautiful or some grand reveal. It can be messy and ugly and raw as long as it is real. That, to me, has always been the first step because the more you put the things you’re struggling with onto paper, the more you can take a step back and see it from outside yourself. In doing so, you are giving yourself the space to feel and remember, to offer an outlet for everything churning about you and within you. These things need a place to go, and you are the best person for the job when it comes to creating a safe place for those things to land. From there, the healing and processing can begin. If you wish, you can also tackle your words through a creative lens and determine how you want to shape, frame, and share your words. I tend to write confessional poetry for it gives me room to turn all of my mess into what makes the most sense to me. It allows me to take my pain, soothe it, and eventually put it back down. Ultimately, the best things you can do are to be unafraid of your truth. Trust your gut. Believe in your art. Take your time. Be gentle with yourself. And write it all down.